When NASA behavioral scientist Jay Hall developed the Moon Landing Challenge in the 1960s, he couldn’t have predicted that decades later, millions of professionals would be “stranded” not on the lunar surface—but in home offices, coffee shops, and Zoom grids across the globe. Yet this classic group decision-making and collaboration exercise — where participants rank 15 survival items after a hypothetical moon landing mission gone wrong — holds profound relevance for today’s remote and hybrid teams.

I first encountered this exercise during a leadership course early in my career. At the time, I dismissed it as a gimmick until I saw how dramatically it exposed gaps in trust, communication, assumptions, and group dynamics. A colleague of mine told the group that he has played this simulation before and he knows the answers. Yet, nobody in the group believed him (maybe because he just joined from a competitor’s company or he didn’t sound convincing). It struck me then that even you know the outcome or you know you’re right, it is futile if you cannot convince your team/group to believe in you.

Here are five lessons from the Moon Landing Challenge that are even more critical in a remote work environment.

The Danger of Overconfidence in Individual Judgment – Especially in Isolation

In the Moon Landing Challenge, participants first rank the items alone, then as a group. Time and again, individuals — especially those with technical backgrounds — assume their solo rankings are superior. But NASA’s data shows that group rankings almost always outperform individual ones. Why? Because no single person holds all the relevant knowledge. And remote work amplifies this risk substantially. Without casual hallway conversations or eye-to-eye exchanges, it’s easy to assume your perspective is superior.

I worked with a remote engineering lead who insisted the team prioritize a complex debugging tool during a product crisis. Confident in his judgment, he made the call without looping in support or customer success. Only later did we learn that users weren’t encountering the bug he’d focused on — they were stuck on onboarding. Had he consulted the team synchronously or even reviewed shared customer logs, he’d have redirected efforts faster. Remote work demands intentional knowledge-sharing. Don’t let physical distance become cognitive distance.

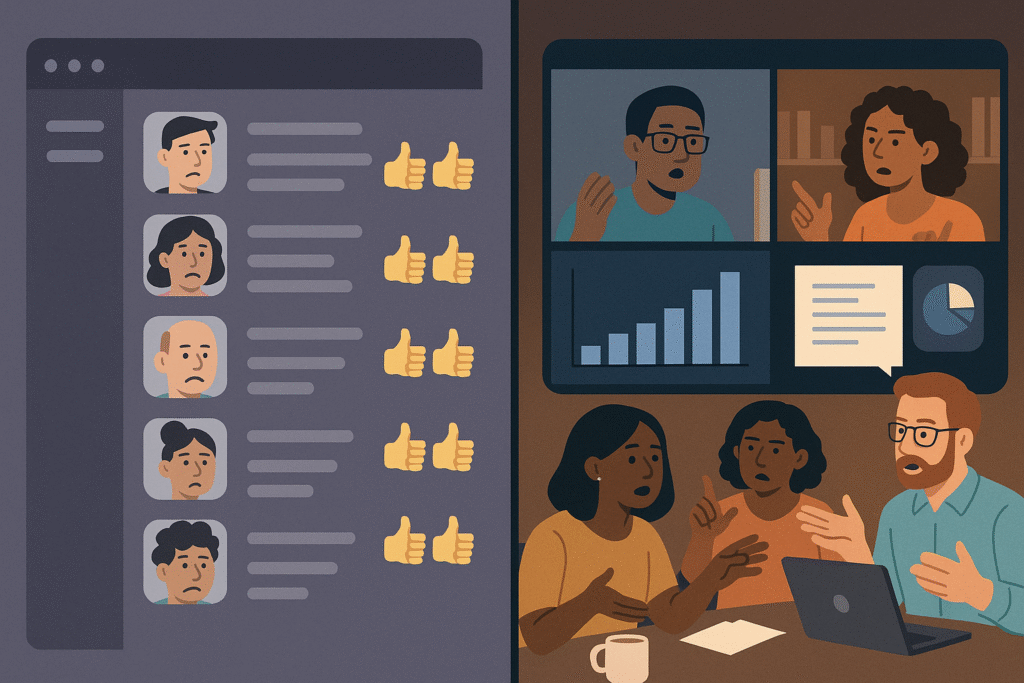

Virtual Consensus Isn’t the Goal — Better Decisions Are

Many teams mistake consensus for success. In the Moon Landing Challenge, the objective isn’t to make everyone happy — it’s to survive. That means prioritizing accuracy over harmony. Healthy conflict, grounded in data and logic, often leads to better outcomes than smooth agreement.

Remote teams often mistake “everyone replied ‘👍’ in Slack” for true alignment. The Moon Challenge reveals a harsh truth: nodding along digitally rarely equals shared understanding. In fact, the exercise shows that groups that engage in respectful debate — challenging assumptions with evidence — consistently outperform those that rush to agree.

On one remote project, our team quickly “agreed” on a launch timeline in a 30-minute call. But two weeks later, marketing, engineering, and design were operating on three different interpretations of that timeline. We’d achieved surface-level consensus without clarity. Now, we use a simple rule: if a decision impacts more than one function, we document the “why” in a shared space and confirm understanding with a quick voice note or Zoom video. In remote settings, clarity must be engineered, not assumed.

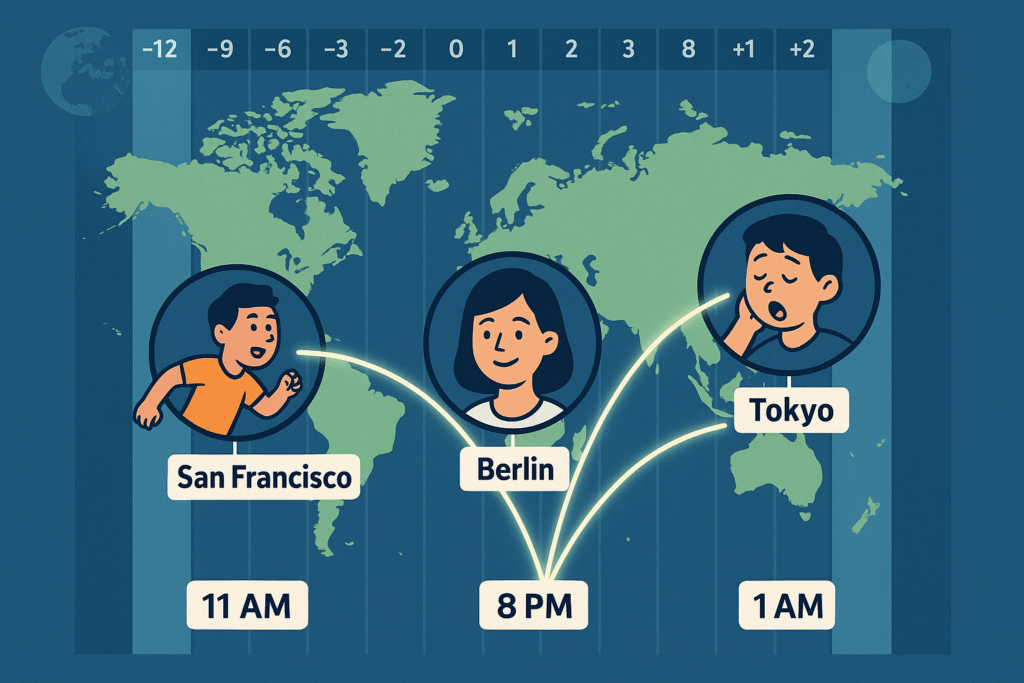

Context Gets Lost in Translation — Rebuild It Constantly

One of the most eye-opening aspects of the challenge is how context dictates value. On Earth, a box of matches seems essential. On the moon? Useless—there’s no oxygen to sustain a flame. In remote work, so are strategies that ignore time zones, communication preferences, or cultural context. The Moon Challenge teaches that value is situational — and remote teams operate in highly variable contexts.

I once managed a global team where a German-based member scheduled a “quick sync” at 1 a.m. local time for an APAC colleague, assuming urgency justified the ask. The APAC teammate, not wanting to seem uncooperative, joined — but contributed little. Later, they shared they’d been too exhausted to think clearly. We’d failed to adapt our “survival strategy” to the real conditions on the ground (or in this case, in different time zones). Now, we co-create team norms: core overlap hours, async-first documentation, and explicit escalation paths. Context isn’t static — it must be continuously updated.

Silent Knowledge Is a Remote Team’s Achilles’ Heel

In the Moon Challenge, teams often lose points not because they lack knowledge, but because they fail to share it effectively. Someone might know that a parachute could double as shelter material, but if they don’t articulate that clearly — or if others dismiss it — the insight is lost. In remote work, this risk multiplies. Critical insights live in private chats, unshared docs, or individual heads.

A client of mine lost a major client because two remote team members each held half the puzzle: one knew the client’s budget cycle; the other knew their feature priorities. Neither connected the dots because they assumed the information was “obvious” or already shared. Now, they hold weekly “knowledge swaps” — 15-minute async updates where each person shares one insight that might help others. Remote work requires deliberate knowledge circulation. If it’s not visible, it doesn’t exist.

Process Is Your Lifeline When Proximity Is Gone

The highest-performing teams in the Moon Challenge aren’t the ones with the smartest individuals — they’re the ones that agree on a decision-making process upfront. They assign roles, agree on how to resolve disagreements, and define what “success” looks like before diving in. This is non-negotiable in remote environments, where ad hoc collaboration leads to chaos.

My own team now begins every project with a lightweight “mission briefing”: What’s our goal? Who decides what? How will we communicate blockers? Where is our single source of truth? This ritual inspired by the structure of the Moon Challenge has prevented countless misunderstandings. In the absence of physical cues and spontaneous check-ins, process isn’t bureaucracy; it’s oxygen.

Final Thought

The NASA Moon Landing Challenge endures not because it’s about space — but because it’s about people. In an era of AI, remote work, and constant disruption, the fundamentals of collaboration, humility, and contextual thinking matter more than ever. Today’s remote workers face their own version of that lunar isolation. But with intentional communication, shared context, and collaborative humility, we don’t just survive. We thrive no matter where we log in from 🙂